I know why someone would keep recipes,

why someone would cut them out of a magazine

and adhere them to index cards,

But I didn't know why my mother’s recipes were glued

to the back of cards already used,

already written on in my father’s handwriting

as he catalogued

the record albums he owned.

Hot mulled wine on one side,

Weill, “Lost in the Stars”

Decca 8028

Todd Duncan

on the other.

Chickpea Dip on one side,

Gounod - “Faust” arias

Music appreciation 20203

on the other.

While my mother is here to tell me

how she used the backs of the cards

because reusing was what you did

because you couldn't simply go buy more

just because you wanted to,

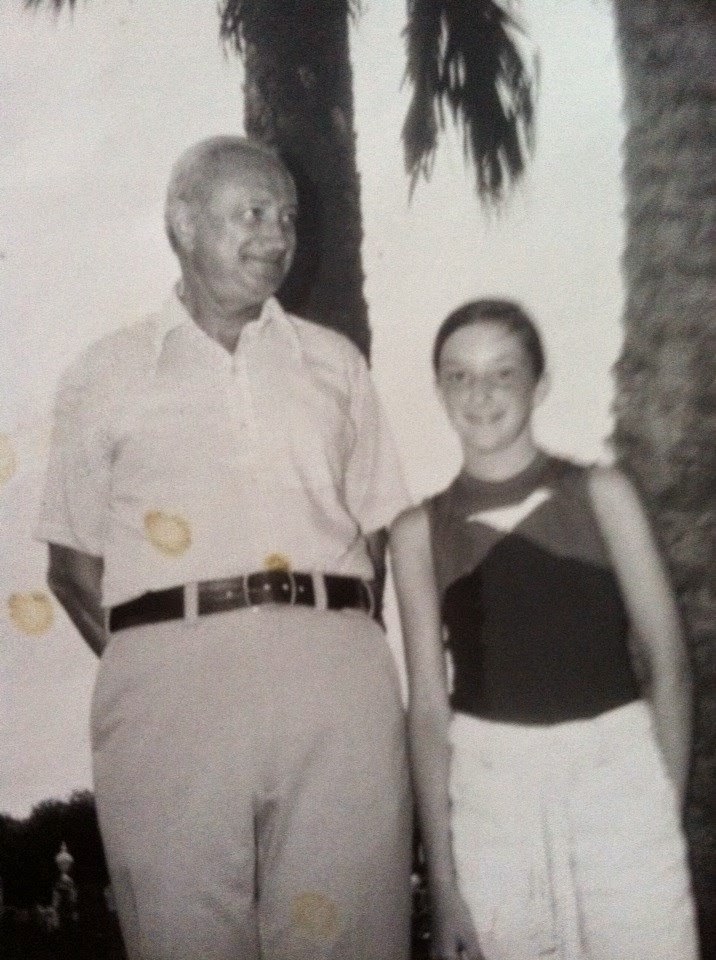

My father is not here to tell me

what it meant

to catalog record albums.

How did he decide on this activity?

How did he choose to buy index cards

and write down every album

and alphabetize them by title

and keep them in a box?

And how did that box one day become my mother’s?

How was it decided

to turn Donizetti - “Lucia de Lammermoor” arias

Royale 1211

Into Pineapple-Yogurt pudding?